For simple strumming patterns the usual ‘du-‘ strumming notation works just fine. But for more intricate rhythms you need a more comprehensive system.

And that’s where slash notation comes in. Slash notation looks a lot like standard musical notation. But it’s a lot simpler. It dispenses with all the notes because you only need it pick up the rhythm.

So this post is a combination slash notation primer and advanced strumming patterns post. Including the famous Mumford strum and the greatest strumming pattern in the world ever.

This post follows on from the ideas in the How to Play Ukulele Strums ebook which covers the basics of strumming and understanding how the fit into a song.

Basic Strums in Slash Notation

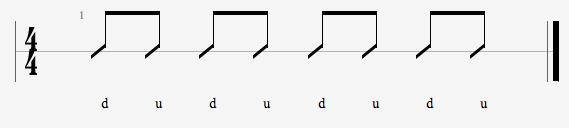

This example is just a simple ‘d u d u d u d u’ strum. Each strum has a vertical line. And each ‘d u’ pair are connected by a single line above them.

BTW the chords in the mp3s are all A – D – A – D unless it says otherwise.

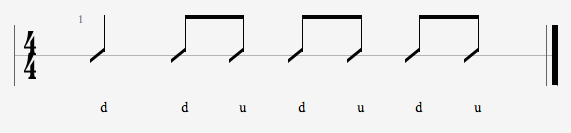

Here’s how it looks when you play a down strum by itself (i.e. you miss out the accompanying up-strum):

That down strum just has the vertical line and isn’t connected to anything. So this one is a ‘d – d u d u d u’ strum.

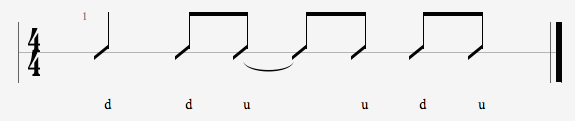

When you miss out a down strum you use a tie. Which looks like a bracket that’s fallen over:

Here the up strum is tied to the next strum. Showing that you just let the chord ring. That gives you the good old ‘d – d u – u d u’ strum.

Rests

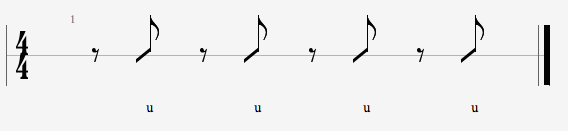

One thing slash notation has that basic strumming notation doesn’t is a way of representing rests. A rest is when you don’t make any sound at all. And if they chord is playing you stop either (by resting one or both of your hands on the strings).

This example – a diagonal line with a ball at the top – uses a rest that lasts the length of either a down- or up-strum. Here each down strum is replaced by a rest. So you play an up-strum. Stop the strings for the length of time you’d usually play a down-strum. Then play another up-strum.

The different length rests look different. You can look at the other rest lengths here.

Also, because the up-strum hasn’t got its down brother, the bar that would go across just goes flaccid.

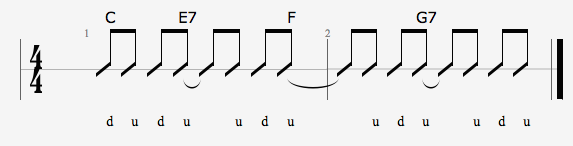

Chord Changes in Weird Places

Slash notation is also great for indicating chord changes that occur in unusual places. You can indicate exactly where the chord changes by referencing the chord above the strum it changes on.

This example starts with a C chord. Changes to E7 on that second up-strum. Then you get a tie so you don’t play the next down-strum. Then you switch to F on the last up-strum of the bar. And that is tied over too. Finally, you have the same deal with the change to G7.

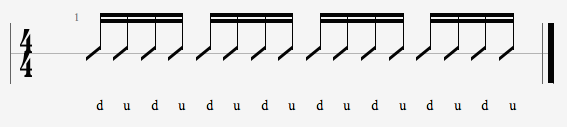

Faster Strums

This example is strummed just like the first example (d u d u d u…) but it’s strummed at twice the speed. So whereas the first example had a ‘d u’ in the space of one click of the metronome, this example has ‘d u d u’ for each metronome click.

Because you’re doubling up the speed you also double up the lines going across the top.

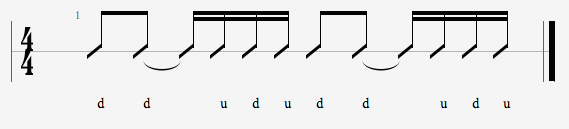

Mumford and Strums

Here’s a strumming pattern that uses some of these ideas. You might recognise it from Mumford and Sons songs like I Will Wait and Little Lion Man.

You’ve got the tie (meaning a missed down strum) combined with a batch of fast strums.

The chords here are Dm and F.

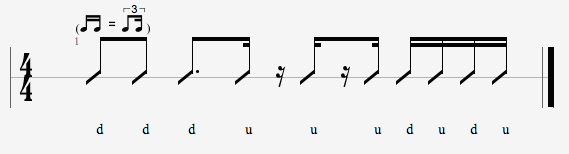

Lust for Life Strum

This is my all-time favourite strum. I throw it in every chance I get. It’s in How to Play Ukulele Strums, How to Play Blues Ukulele and Ukulele for Dummies. And now it’s here.

You’ll recognise the fast strumming. And the rests should look sort of familiar too. But these have two balls rather than the more Hitlerian one ball we saw before. That indicates they’re twice as fast. So they take up the space of one of the fast down- or up-strums. In this case, it’s down-strums both times.

One new thing: there’s a dot after one of the notes. That’s telling you to increase the length of the note by half. So originally it’s half a beat long. Add on half again. Now it’s three quarters of a beat long. With that fast up-strum filling up the rest of the beat.

There is one more thing: the little equation at the top left. That’s indicating swing time. But that’s a post for another day.

Here’s how the strum sounds at a slow tempo on a B chord:

.

And here’s how I used it in the blues ebook for an uptempo jump blues:

.

Links

If you want to learn more about strumming check out my ebook How to Play Ukulele Strums

This work by Ukulele Hunt is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Thank you for the aural and visuals. Very, very helpful.